Owen Connors

YEAR OF RESIDENCY

May - August 2023

Owen Connors - Educational Resource

Gate XVI Owen Connors x Lukrecya Craw - July 2023

Owen Connors is an artist and writer based in Tāmaki Makaurau. They studied at Elam School of Fine Arts, Auckland University and The Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics, Naropa University, Colorado.

Recent exhibitions include, your cart and plow over the bones of the dead, 2022, Robert Heald Gallery; for the feral splendour, Physics Room; Incubations, Robert Heald Gallery; and For Future Breeders, Parasite, Tāmaki Makaurau.

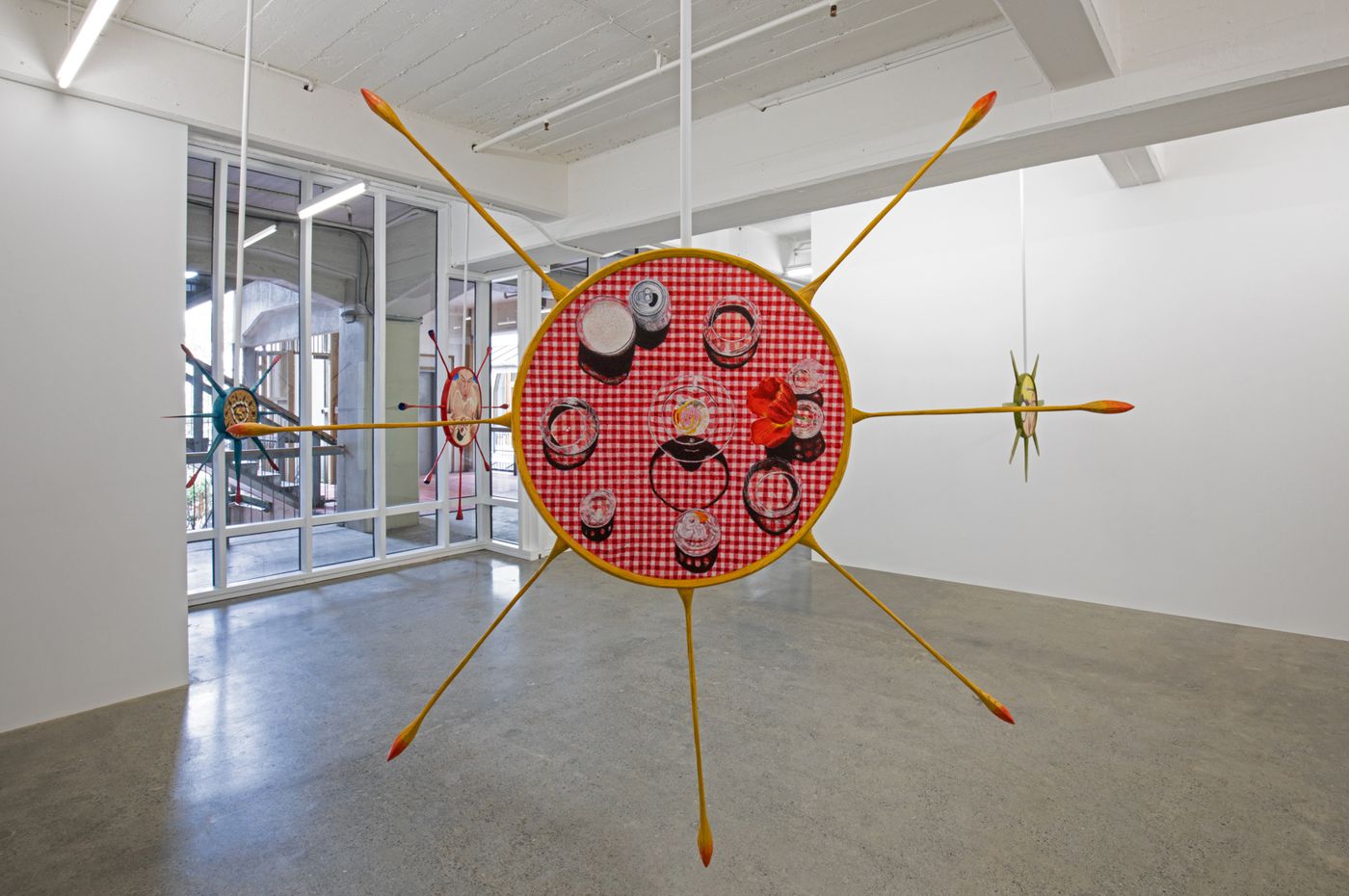

Image: Owen Connors, Libations, 2021, egg tempera on board, hand-carved lacquered ash frame. Installation view, Robert Heald Gallery.

Land of doubts & shadows (3), 2024, egg tempera on birch, oxidised custom steel frames, scagliola, 2120 x 930mm (Photo: Jennifer French)

Land of doubts & shadows (1), 2024, egg tempera on birch, oxidised custom steel frames, scagliola, 2120 x 930mm (Photo: Jennifer French)

Land of doubts & shadows (1), 2024, egg tempera on birch, oxidised custom steel frames, scagliola, 2120 x 930mm (Photo: Jennifer French)

Land of doubts & shadows (2), 2024, egg tempera on birch, oxidised custom steel frames, scagliola, 2120 x 930mm (Photo: Jennifer French)

Land of doubts & shadows (2), 2024, egg tempera on birch, oxidised custom steel frames, scagliola, 2120 x 930mm (Photo: Jennifer French)

Land of doubts & shadows (3), 2024, egg tempera on birch, oxidised custom steel frames, scagliola, 2120 x 930mm (Photo: Jennifer French)

I grew up hearing stories of peat fires which would burn underground, emerging to consume the dry grass, barns, houses, a school building on the surface. These fires were often ignited by burnoffs on the farms, or summer lightning that ran down through the tree roots into the earth. Even the word ‘burnoff’, unremarkable to me at that time, has a scary glow now—early farming in New Zealand involved so much burning(1). The fires I heard about then were already deep in the past. They would have been in the time of my grandparents, Pākehā dairy farmers in the Waikato where over one million acres had been confiscated by the government during the 1860s (2), locked in a kind of grinding battle with the swampy and forested land, which was cleared and drained, imported grass seed often planted directly into the ash. I’ve read about the high suicide rate for farmers in New Zealand, both then and now. Hard to sit with, my growing awareness that the routine violence of the colonial project also included the brutalising of its own agents, some of them farmers like my ancestors. I watch an archival newsreel about the peat fires from from the 1940s (3) and see the men digging trenches, the only way to halt the fires’ progress, squinting through smoke from smoldering raupō in the foreground. It’s a lot of things at once: gothic, upsetting, and local history.

I share this in a text about Owen Connor’s Land of doubts and shadows as Pākehā colonial histories related to farming are something I think about when I see their recent work. Owen and I also share ancestry from Ireland—another island of peat and bog, shelves of limestone and greywacke—and an interest in the pre-christian Celtic stories of that place. The setting for Land of doubts is a stony non-specific underground, with individual scenes pivoting on conflict, labour, and sacrifice. What could be more politely contained as allegory in these works instead butts uncomfortably against the historical record. Specifically, the works invoke patterns of violence associated with subduing the land, and the assertion of a national identity hinged on agricultural productivity at the cost of methodical environmental destruction.

In this work Owen drew from the Irish epic The Tragedy of the Brothers of Tuireann, a horror-genre narrative in which three brothers set out to kill their father's enemy, Cian. Cian shapeshifts into a pig to evade them, but the brothers shapeshift into dogs and hound him to death. They dismember his body and attempt to cover up their crime. As éraic or retribution for the murder the brothers are made by Cian’s son, Lugh, to perform a series of impossible tasks which eventually lead to their deaths (4). As Owen has suggested in other places, the story offers a perspective on how the past inevitably shapes us, on reckoning with historical obligations, and on an extreme form of reparative justice (5).

Owen’s work resists legibility in many ways. In Land of doubts and shadows there is a sense of superabundant narrative without any obvious way to access it; individual images appear symbolically heavy-laden; a pig smiles enigmatically. What first appear to be volcanic rocks attached to the frames of the works are actually fake marble scagliola, a plaster composite most popularly used in the 17th century. Figures in the works turn their backs to us, intricately inscribed pages of text and music are readable but hard to assimilate into a cohesive story, and the vertically oriented works themselves are double-sided, two-faced, and able to be rotated: one can never view the whole as a single image.

Psychoanalytic theory offers one way of navigating this state of overload or excess, defined by writer and critic Jacqueline Rose as “an infinitude of traces without [...] an inventory”, the work of a psychoanalytic reading being, in Rose’s words, “to produce differences where at present there are none (6)". Certainly, the sense I have with Owen’s work is that this is a strategic evasion of the methodical decoding associated with conventional art historical analysis, in favour of a more divergent or versatile form (7), extended by associations with the vers of queer vernacular. In the spirit of this I look up the derivation of the word versatile, finding the Latin versātilis (“turning easily”), with links to versō (“I turn, change”), and vertō (“I turn”).

To turn, to change. I argue that what could in this work be read as a kind of acting out, a turning on expectations of legibility, might be more usefully understood as the intentional disruption or reversal of linearity, and as such a refusal to reproduce the historical violence of received narratives. Perhaps the disquietude produced by this work is also an effect of its queering of heteronormative history, that it stages a turning toward the present-future where not only the stories as they are told, but our own bodies are replete with potential to change. I’m interested in how this vers or versatile reading may allow us to read the work, the present, and ourselves anew. Go further—I'm suddenly hopeful—look into a future that is in fact not worse than the present; does this mythic, campy, even over-burdened narrative hold the possibility of identifying a different way to process colonial history, to look it in the face and ask for the story to turn out differently?

Return to the story of the brothers of Tuireann, and the idea of éraic that they must undertake to atone for the killing of Cian. There are nine tasks, initially laid out in simple terms that belie their impossibility. The brothers must collect “three apples, the skin of a pig, a spear, two steeds, a chariot, seven pigs, a whelp, a cooking spit, and three shouts on a hill” (8). It’s the final labour that interests me the most: a site specific performance, a howl of insubordination or fearlessness. The hill in question belongs to Miodhchaoin, with whom the brothers have an existing family feud. To go to this hill is to invite danger, to go there and shout aloud—in defiance, in pain or song—is to tip the balance of mutual historical animosity into violent action, and it is where the brothers are ultimately killed by the sons of Miodhchaoin and the story ends.

I don’t mean to map this gory narrative too precisely onto the imagery in Owen’s paintings, or render it ‘queer’ in some metaphorical way, which would just perform the same act of decoding that I've proposed they counter. The Brothers of Tuireann is a story, as feral and resistant to being co-opted as it is enduring. However, borrowing some of the epic tragedy’s momentum directed me to thinking more closely about colonising relationships to the land, specifically those that involve violence, fear, doubt, shame, patriarchal masculinities or othering in the contemporary context. Elements of these relationships play out in the underground setting of Owen’s work, where we see pairs of men wrestling in the water and urinating on the shore, where a sheep has been messily slaughtered, where one bird is caged and another is chased with a knife. Each of these moments is presented as a point of otherworldly plot tension, while at the same time an event or scene that would not be unfamiliar on farms across the country.

These everyday acts of violence also make me think of the longer, slower impacts of colonialism on the health of the soil itself. Globally the most obvious example of this may be through monocultural farming, ‘a colonialist invention’ that systematically impoverishes the fertility of the land (9). Plenty of local examples too: the legacy of leachate from landfill sites such as on Ngāti Awa whenua in Whakatāne (10); the aggressive mining on the West Coast of the South Island being proposed by the current government (11); the quantities of methane and nitrous oxide produced by farming in New Zealand.

Formally too, the works confront us with the presence of what lies beneath the soil and geological strata. In the artist’s words, these tall works “force the plane of engagement into a vertical one (connecting the above with the below). Their orientation engages the body in their imagined landscapes, as opposed to looking out at a scene, making the viewer an agent in the work and refusing a passive relationship with the land” (12). We see feet, the face of a curious dog, a bird shitting, bees and plants above ground; below ground is where the action occurs though, amid egg shaped grey stones and beside a tannin-coloured river. This is where the lasting and perhaps least perceptible human violence unfolds, deep in the bowel of the earth itself.

In the work there’s light down there too though; each scenario is lit up, brightly if not warmly, or relies on shadows to reveal the action. Further, the use of egg tempera, low in pigment and light-fast, means that a kind of lucency is emitted or bounced from the painting itself: something is alive, aglow here in the darkness and under the soil. As in many of Owen’s works, all the male figures are modelled on the artist. The series of people who inhabit this work all look related, or put another way, everything that ‘happens’ in this work has already been undertaken or enacted by the artist themselves. Perhaps as much an act of self-reflection, collective accountability, as it is its own wordless howl on a hill, a sound that hangs in the air above the work.

What else becomes imaginatively accessible when we return to stories, family accounts or larger mythic stories like this, when we delve into the layers of soil and stone beneath our feet? I don’t see the work of this painting or any painting as telling us what to do in any direct way, but nor do I think this limits the power of the work to engender new patterns of thought, to re-activate the historical record and to ‘produce differences where at present there are none’ in the future. All these fathers in the story, and I think of a photo of my own dad, returning for the first time as a 40-something year old to Tobercurry, Sligo in west Ireland where his dad was born. He’s standing where a house used to be, red-faced from the wind and the walk, but also looking slightly sheepish or maybe just young. I can’t really know what he was thinking, but I wonder if a reckless shout would better express it. A feeling of obligation to his own history, to our history, a feeling that he is standing on peaty ground and rocky substrate, on decomposing plant material and crackling new minerals, on uneasy yet transformative stories for which words will not be enough.

Artist Artworks

Owen Connors

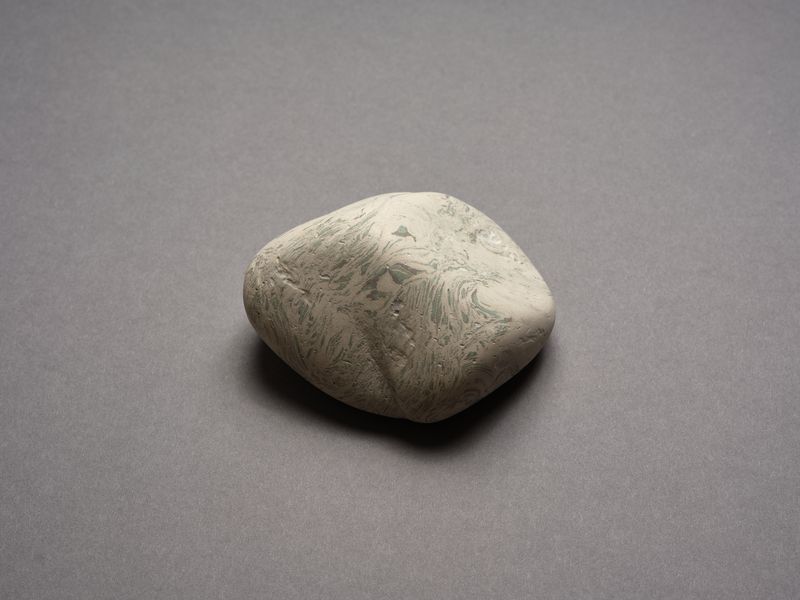

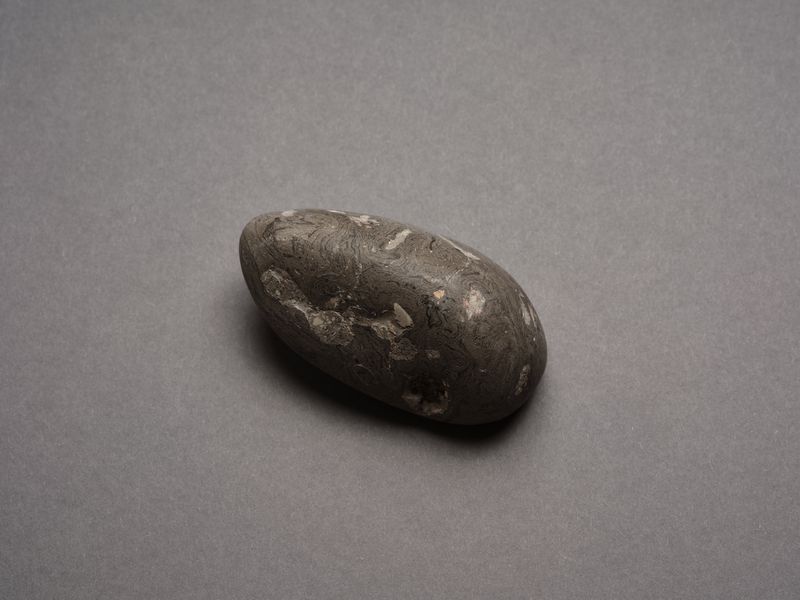

Rock 10

2024

scagliola, conservator’s wax, earth magnet

70 x 45 x 40mm

SOLD

Image: Sam Hartnett

Scagliola is a composite material that came to prominence in Tuscany in the 17th century and is made of plaster, rabbit skin glue and pigment. This material was generally used for columns and interior walls and fake marble inlay on altarpiece bases and tables. Made with the assistance of Katherine Rutecki.

They were made in conjunction with the Walter's Prize works 'Land of Doubts and Shadows', 2024.

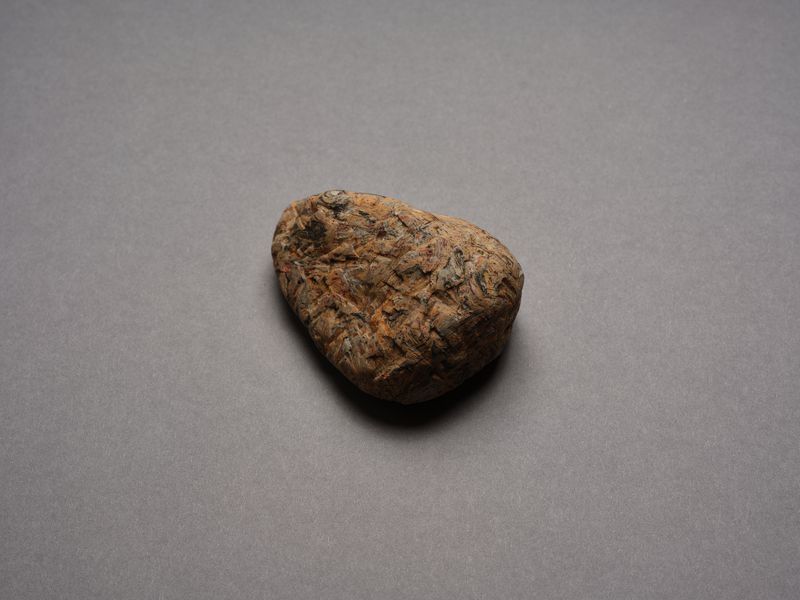

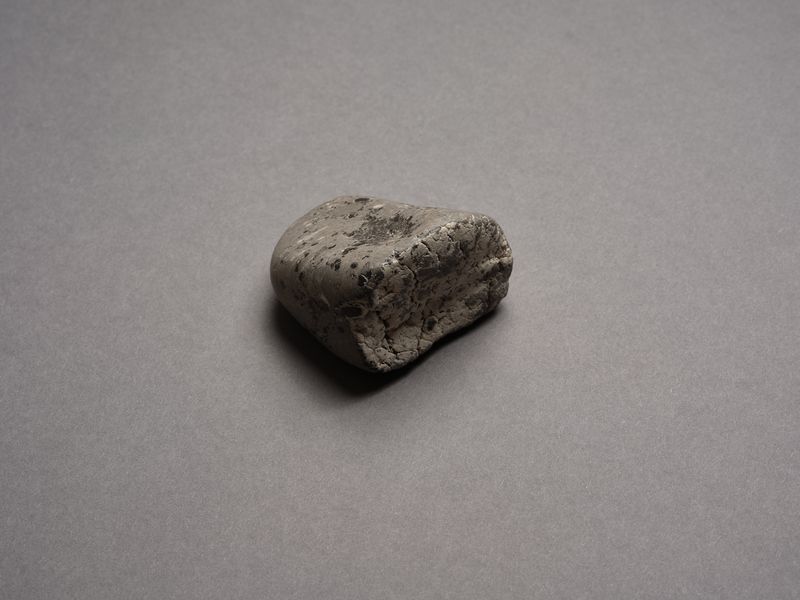

Owen Connors

Rock 5

2024

scagliola, conservator’s wax, earth magnet

65 x 55 x 50mm

$200

Image: Sam Hartnett

Contact us to purchase this edition.

Scagliola is a composite material that came to prominence in Tuscany in the 17th century and is made of plaster, rabbit skin glue and pigment. This material was generally used for columns and interior walls and fake marble inlay on altarpiece bases and tables. Made with the assistance of Katherine Rutecki.

They were made in conjunction with the Walter's Prize works 'Land of Doubts and Shadows', 2024.

Owen Connors

Rock 4

2024

scagliola, conservator’s wax, earth magnet

90 x 65 x 40mm

SOLD

Image: Sam Hartnett

Scagliola is a composite material that came to prominence in Tuscany in the 17th century and is made of plaster, rabbit skin glue and pigment. This material was generally used for columns and interior walls and fake marble inlay on altarpiece bases and tables. Made with the assistance of Katherine Rutecki.

They were made in conjunction with the Walter's Prize works 'Land of Doubts and Shadows', 2024.

Owen Connors

Rock 3

2024

scagliola, conservator’s wax, earth magnet

85 x 70 x 40mm

SOLD

Image: Sam Hartnett

Scagliola is a composite material that came to prominence in Tuscany in the 17th century and is made of plaster, rabbit skin glue and pigment. This material was generally used for columns and interior walls and fake marble inlay on altarpiece bases and tables. Made with the assistance of Katherine Rutecki.

They were made in conjunction with the Walter's Prize works 'Land of Doubts and Shadows', 2024.

Owen Connors

Rock 2

2024

scagliola, conservator’s wax, earth magnet

75 x 55 x 40mm

SOLD

Image: Sam Hartnett

Scagliola is a composite material that came to prominence in Tuscany in the 17th century and is made of plaster, rabbit skin glue and pigment. This material was generally used for columns and interior walls and fake marble inlay on altarpiece bases and tables. Made with the assistance of Katherine Rutecki.

They were made in conjunction with the Walter's Prize works 'Land of Doubts and Shadows', 2024.

Owen Connors

Rock 11-15

2024

scagliola, conservator’s wax, earth magnet

dimensions variable

Collection of McCahon House Trust

Image: Sam Hartnett

Scagliola is a composite material that came to prominence in Tuscany in the 17th century and is made of plaster, rabbit skin glue and pigment. This material was generally used for columns and interior walls and fake marble inlay on altarpiece bases and tables. Made with the assistance of Katherine Rutecki.

They were made in conjunction with the Walter's Prize works 'Land of Doubts and Shadows', 2024.

Owen Connors

Rock 9

2024

scagliola, conservator’s wax, earth magnet

75 x 40 x 35mm

SOLD

Image: Sam Hartnett

Scagliola is a composite material that came to prominence in Tuscany in the 17th century and is made of plaster, rabbit skin glue and pigment. This material was generally used for columns and interior walls and fake marble inlay on altarpiece bases and tables. Made with the assistance of Katherine Rutecki.

They were made in conjunction with the Walter's Prize works 'Land of Doubts and Shadows', 2024.

Owen Connors

Rock 8

2024

scagliola, conservator’s wax, earth magnet

55 x 50 x 35mm

$200

Image: Sam Hartnett

Contact us to purchase this edition.

Scagliola is a composite material that came to prominence in Tuscany in the 17th century and is made of plaster, rabbit skin glue and pigment. This material was generally used for columns and interior walls and fake marble inlay on altarpiece bases and tables. Made with the assistance of Katherine Rutecki.

They were made in conjunction with the Walter's Prize works 'Land of Doubts and Shadows', 2024.

Owen Connors

Rock 7

2024

scagliola, conservator’s wax, earth magnet

80 x 50 x 40mm

SOLD

Image: Sam Hartnett

Scagliola is a composite material that came to prominence in Tuscany in the 17th century and is made of plaster, rabbit skin glue and pigment. This material was generally used for columns and interior walls and fake marble inlay on altarpiece bases and tables. Made with the assistance of Katherine Rutecki.

They were made in conjunction with the Walter's Prize works 'Land of Doubts and Shadows', 2024.

Owen Connors

Rock 6

2024

scagliola, conservator’s wax, earth magnet

85 x 55 x 35mm

SOLD

Image: Sam Hartnett

Scagliola is a composite material that came to prominence in Tuscany in the 17th century and is made of plaster, rabbit skin glue and pigment. This material was generally used for columns and interior walls and fake marble inlay on altarpiece bases and tables. Made with the assistance of Katherine Rutecki.

They were made in conjunction with the Walter's Prize works 'Land of Doubts and Shadows', 2024.

Owen Connors

Rock 1

2024

scagliola, conservator’s wax, earth magnet

90 x 60 x 35mm

SOLD

Image: Sam Hartnett

Scagliola is a composite material that came to prominence in Tuscany in the 17th century and is made of plaster, rabbit skin glue and pigment. This material was generally used for columns and interior walls and fake marble inlay on altarpiece bases and tables. Made with the assistance of Katherine Rutecki.

They were made in conjunction with the Walter's Prize works 'Land of Doubts and Shadows', 2024.